Wednesday, June 8, 2011

Health Care Costs And The Third-Party Payer Problem The real heart of the matter.

The Cato Institute’s Daniel Mitchell makes this comment in a blog post on health care costs and Medicare reform:

I don’t pretend to be an expert on healthcare, but I am firmly convinced that third-party payer is one of the big reasons for rising costs and pervasive inefficiency in the healthcare sector. When we buy goods and services with our own money, we try to get maximum value, and producers respond by trying to be efficient as possible.

In the healthcare sector, by contrast, we shop with other people’s money. Or, to be more technical, we shop in an environment where government policies result in us bearing very little out-of-pocket cost for each additional increment of health care.

Mitchell does have a point. For most people with health insurance, a visit to the doctor typically ends up costing no more than a small co-payment. For other medical services, some people are responsible for a typically small deductible when using insurance to pay for tests, procedures, and prescriptions. Larger charges only tend to arise when, for some reason, an individual ends up receiving care from an institution or physician that isn’t part of the insurance network, although with most large insurance networks like Blue Cross/Blue Shield that seems to be much less of an issue than it used to be. For the typical person in a typical year, though, there’s almost no thought given to the cost of a medical procedure (why not go to the doctor for those sniffles when it only costs you a $10 co-pay?).

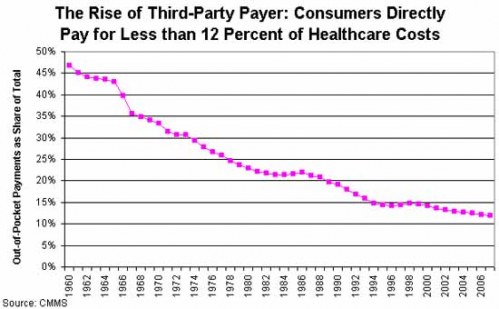

It didn’t always work this way. For a long time, health insurance, including insurance provided through employers, typically only covered major medical procedures and hospitalization (I remember terms like “major medical” and “hospitalization” being used to described health insurance as late as the 1970s). Over the years, though, insurance has come to cover more and more “routine” medical expenses, and consumers have become more and more unaware of the actual cost of their health care, to the point where now just 12% of health care costs are paid directly by consumers:

When consumers are insulated from the cost of a good or service, they aren’t going to take the price of that good or service into account when deciding whether or not to purchase it, which means that the normal supply-demand price mechanism isn’t going to work. In the long run, this means prices will go up. Of course, it’s true that health care itself is a good that isn’t necessarily subject to the same market prices as, say, groceries. We all want to live forever, and when we’re sick we want to feel better. Nonetheless, when someone else is paying the bill and, as the chart above shows right now someone else (the government and private insurance) is paying 88% of the bill on average, consumers have every incentive to use as much health care as they can. The consequences are inevitable:

When consumers share in the cost of their health care purchasing decisions, they are more likely to make those decisions based on price and value. Take just one example. If everyone were to receive a CT brain scan every year as part of their annual physical, we would undoubtedly discover a small number of brain cancers much earlier than we otherwise would, perhaps early enough to save the patient’s life.

But given the cost of such a scan, adding it to everyone’s annual physical would quickly bankrupt the nation. But, if they are spending their own money, consumers will make their own rationing decisions based on price and value. That CT scan that looked so desirable when someone else was paying, may not be so desirable if you have to pay for it yourself. The consumer himself becomes the one who says no.

Think of it this way. If every time you went to the grocery store, someone else paid 87 percent of your bill, not only would you eat a lot more steak and a lot less hamburger – but so would your dog. And food costs would go up for everyone.

(…)

The RAND Health Insurance Experiment, the largest study ever done of consumer health purchasing behavior, provides ample evidence that consumers can make informed cost-value decisions about their health care. Under the experiment, insurance deductibles were varied from zero to $1,000. Those with no out-of-pocket costs consumed substantially more health care than those who had to share in the cost of care. Yet, with a few exceptions, the effect on outcomes was minimal.

And, in the real world, we have seen far smaller increases in the cost of those services, like Lasik eye surgery or dental care, that are not generally covered by insurance, than for those procedures that are insured.

In fact, a study by Amy Finklestein of MIT suggests that nearly half of the per capita increasing health care spending is due to increased health insurance coverage.

There are some alternatives available, but they are minimal and not generally favored by the law. A combination of high-deductible insurance, combined with a Medical Savings Account similar to an IRA, for example, would allow consumers to maintain coverage for major expenses like surgery and expensive diagnostic tests, which using the funds the MSA to cover more routine expenses live office visits, blood tests, and prescriptions. It might not be the answer for everyone, but it would go a long way toward removing the third-party payer problem and the upward pressure it has placed on health care costs over the years.

No comments:

Post a Comment