11/2/2014

Seizing, keeping more

source

Companion Article: Turning crime into cash: How forfeiture law works

Who says crime doesn't pay?

From left, Jammie, Makiah, Tom and Barb Spring at their Quarryville home.

Barbara and Ralph Spring are struggling to raise their two grandsons after their daughter, Jessica Marie Crawford, died from a drug overdose last year.

The Quarryville couple wish they had their daughter's Jeep Cherokee to take the kids back and forth to sports events. Or, they wish they could have sold it and kept the money for the kids' college education.

Somehow a drug dealer they don't even know ended up with their daughter's vehicle. After he was arrested, he surrendered the Jeep to county officials through a process called “civil asset forfeiture.” The county sold it and kept the proceeds; the money will be used to fund the war on drugs here.

The Springs, and others like them, just happened to get caught in the crossfire.

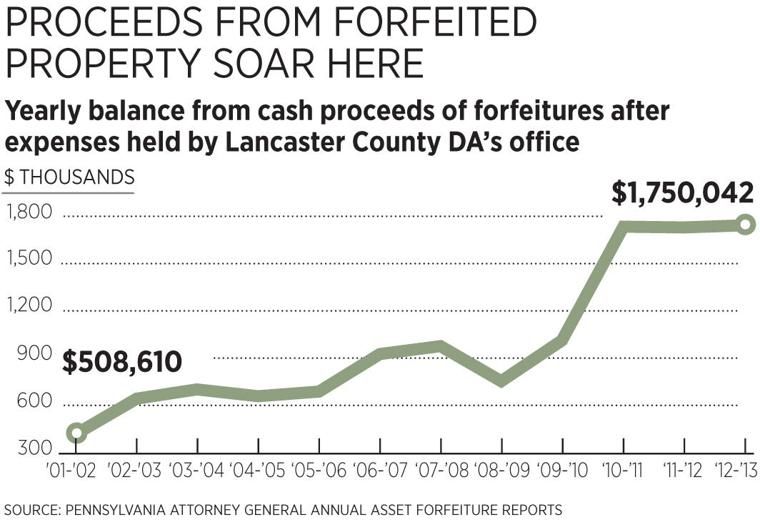

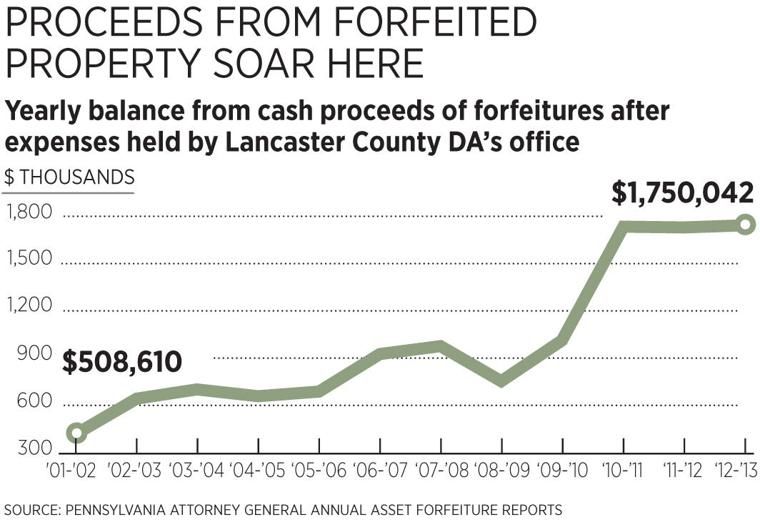

State forfeiture law allows county officials to seize money or property believed to be connected to crime. Here in Lancaster County forfeitures are on the rise. The Lancaster County District Attorney’s Office has generated millions in forfeiture proceeds in recent years and is sitting on a $1.75 million surplus.

Most of the money came from drug dealers’ pockets. But not all of it.

Some came from a mother whose son, living at home, was arrested for dealing drugs. Officers went into her purse and took $300 from her.

More than $1,300 came from a woman found dead in her apartment, after officers called to check on her welfare and found a small amount of marijuana and pain pills. Officers even seized money they found in her car.

Critics denounce forfeiture as “policing for profit.” Law enforcement doesn’t have to prove that cash and other property are connected to crime; instead, the property owner has to prove they aren’t.

While the law was designed to crack down on major drug criminals, an LNP review of hundreds of recent forfeiture files show it’s more often used against low-level dealers, casual users — and sometimes people never charged with a crime.

District Attorney Craig Stedman calls the law an effective tool, allowing his office to strip assets from drug dealers and fund enforcement.

“If it’s being abused as a means of generating revenue, then you have a problem,” Stedman said.

But Lancaster defense attorney Steven Breit says forfeiture is “in vogue” around the country. “In this day and age, where you have funding shortages all over the U.S. , what better way to fill your coffers than to go full-bore on asset seizures?” he asked.

“The poor schmuck on the street who forfeits $400 or $500 — he’s probably not going to challenge it.”

Seizing, keeping more

If police pull you over and find a sizable sum of money — and believe it’s connected to crime — they can seize it. Later — after criminal charges, if any, are resolved — the District Attorney’s office will file a “petition for forfeiture,” asking the courts to let the office keep the assets.

From 2004 to 2011, an average of 149 forfeiture petitions were filed here annually. In 2012 and 2013, that figure spiked to 236 and 233, respectively; through the end of September 2014, 211 petitions were filed.

The surge resulted, in part, Stedman said, because “a few years ago, the city police provided us with a long list of old cases they never sent over to us” to complete the civil forfeiture process.

The Pennsylvania Supreme Court may soon require forfeitures to be filed in a more timely manner.

Stedman said he’s issued a moratorium on older cases until the court makes a decision.

Stedman said he’s issued a moratorium on older cases until the court makes a decision.

According to the Pennsylvania Attorney General’s Office, Lancaster County generated $2.4 million in forfeiture revenue from fiscal years 2010-11 to 2012-13. Only Philadelphia ($15.3 million), Allegheny ($2.9 million) and Montgomery ($2.8 million) counties generated more.

Some revenue comes from shared state or federal forfeitures. The majority comes in the form of cash seized or generated via an annual auction of forfeited items, which can make for a strange sale list. (See related story).

State law restricts how the money can be spent. Here, it helps fund the Lancaster County Drug Task Force — which conducts raids that lead to arrests, seizures and forfeitures — and pays for police education, training and other expenses.

Calls to officials with the Drug Task Force were not returned.

Stedman's office ended the 2012-13 fiscal year — the latest for which statewide figures are available — with a surplus of $1.75 million in forfeiture funds. That was the second-highest forfeiture-related surplus in Pennsylvania.

Stedman has no plans to spend it down rapidly: “I need to be responsible with the budget,” he said.

Small amounts add up

The big numbers can be misleading. An LNP examination of more than 700 petitions filed since 2012 shows a majority involve small amounts of cash — often under $500.

In most cases, the assets belong to people selling drugs. But not always.

In Columbia in July 2013, members of the Drug Task Force seized $640 from Steven Sanford, no age available, who was driving in a car with someone who had several bags of cocaine on him. Sanford had no drugs on him and wasn’t charged. Stedman’s office has asked the courts to keep his money.

In a 2011 case, Drug Task Force members raided the basement of a Manheim home and charged Shawn Lee Campbell, then 24, who was living there, with possession of drugs with intent to distribute, to which he eventually pleaded guilty. During the raid, officers went upstairs and into the purse of Campbell’s mother, Theresa Campbell, and found $300. She wasn’t charged, but officers seized the money.

In at least one case, officials took money from a dead person.

In 2007, Lancaster city police found Jacqueline Denlinger, 56, dead in her Judie Lane apartment. The petition for forfeiture, filed in 2012, states that officers were searching for emergency contact information when they found 66.3 grams, or 2.3 ounces, of marijuana and several bottles of Vicodin.

They also found $1,170.30 in Denlinger’s vest pocket. They seized it, along with another $186.37 found in her car.

As with other petitions for forfeiture, the property owner was given 30 days to respond.

As required by law, Stedman’s office ran a newspaper legal ad seeking anyone with an interest in the money. “No one contacted us or opposed so the court ordered the forfeiture,” he said.

“Obviously, there was a nexus between the cash and drugs. We followed the law.”

“Obviously, there was a nexus between the cash and drugs. We followed the law.”

In other cases, “all these individuals also have the right to request a return of property at any time,” Stedman said. “We do not have unchecked authority to forfeit anything without process, and it is improper to characterize it as simply taking people's money,” he said. “A judge has to authorize each seizure.”

Growing criticism

Nonetheless, nationwide a growing chorus of critics is blasting forfeiture laws.

In a Washington Post op-ed last month, John Yoder and Brad Cates — two former Justice Department officials who helped create the asset forfeiture initiative in the 1980s — wrote, “Law enforcement agents and prosecutors began using seized cash and property to fund their operations, supplanting general tax revenue, and this led to the most extreme abuses: law enforcement efforts based upon what cash and property they could seize to fund themselves, rather than on an even-handed effort to enforce the law.”

The Institute for Justice, a Libertarian think tank, is helping to underwrite a class action suit claiming police and prosecutors in Philadelphia conspired to deprive people of their property and their right to due process.

“We see a lot of cases in which the property that is seized is disproportionate to the amount of drugs found,” said Darpana Sheth, an attorney with the institute.

Local police say they don’t conduct random stops, searching for contraband.

“If you can imagine the number of people stopped for minor offenses, if we were doing seizures for all of them it would be a red tape nightmare,” said Keith Sadler, chief of the Lancaster City Bureau of Police.

But he supports the idea: “Most people won't have any sympathy for a drug dealer who says, ‘They took my $5,000!' ” he said. “Yes — they should.”

Stedman agreed, saying that using drug money and assets to fight drugs makes sense.

“The more forfeitures, the more we can do with the Drug Task Force,” he said.

“And if we can stop people from selling drugs to our children, and save somebody’s life, my general philosophy is: Let’s do more.”

Yet not every case is so clear cut.

Jessica Marie Crawford was in rehab, trying to kick her heroin habit, when she found out Gali M. Ortiz-Mangual, who had been driving her Jeep, had been arrested and charged with selling drugs. She told her mother, Barbara Spring, to try to get her vehicle back.

Spring had no idea where to start. Had she known, she might have checked the classified ads, where the District Attorney’s Office published a brief legal notice stating that anyone with a legal claim to the vehicle should come forward.

But Spring and her husband missed the announcement, and the Cherokee became county property.

She was stunned to find out a convicted drug dealer could forfeit a car that wasn’t his — and that the county would take it.

“If they wanted to contact Jessica's family, they could have done so easily," Spring said. “We've had the same phone number for more than 20 years.”

source

Companion Article: Turning crime into cash: How forfeiture law works

No comments:

Post a Comment