7/15/2014

Across the United States, law enforcement agencies are becoming more militarized, according to a recent American Civil Liberties Union report. The Journal begins today a series about how the Winston-Salem Police Department and the Forsyth County Sheriff’s Office use their respective SWAT teams. Today, an overview of the use of SWAT in Winston-Salem.

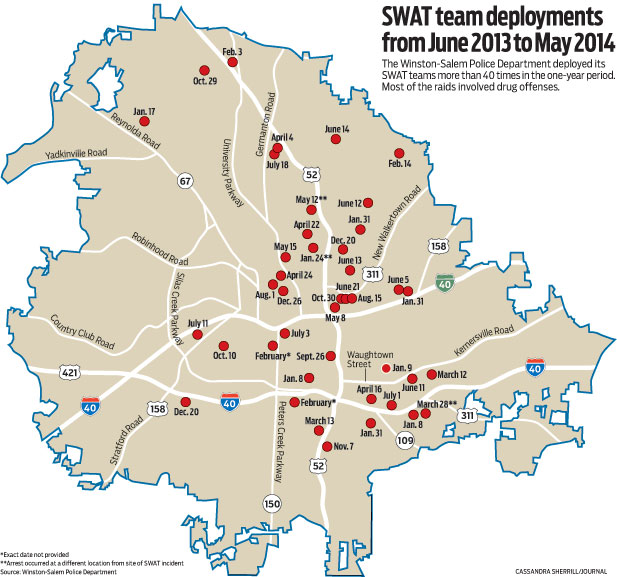

The Winston-Salem Police Department deployed its SWAT team in the city more than 40 times during the year ending May 31, according to documents obtained by the Winston-Salem Journal through public record requests.

One of those deployments distinctly illustrates the challenges facing law enforcement: On Feb. 3, Christopher Jenkins, armed with a handgun, was holed up in a motel off University Parkway, saying he would harm his hostage, Andrew Menjivar, who is Jenkins’ brother.

To get them out, the police department called on SWAT, or Special Weapons and Tactics team.

This is what the team does. According to its standard operating procedures, the team deals with “unusual occurrences.” It deals with “emergency and high risk incidents,” such situations involving a hostage or an active shooter.

And it has the armor. The SWAT team has special equipment, including an armored rescue vehicle known as the BEAR, or ballistic engineered armored response vehicle. Surveillance equipment includes binoculars and cameras. SWAT teams can force their way through a door with an explosive device known as a flash-bang grenade. Team members receive continuous training in such areas as bioterrorism, raid planning and civil disorders, among other scenarios. Training has also included advanced sniper shooting.

On Feb. 3, the SWAT deployment worked.

After nearly 29 hours of negotiations, Jenkins surrendered. Police arrested both men. The standoff ended without bloodshed.

But, as it turns out, the Feb. 3 standoff is not the norm. Police officials rarely use the SWAT team for those types of unusual occurrences. In fact, the SWAT team has other “special assignments,” according to its standard operating procedures, such as providing protection for “VIP and dignitary support” and helping in the “apprehension of criminal offenders.”

Many of the SWAT deployments in the past year involved drug offenses and apprehending those criminal offenders, according to the documents obtained by the Journal.

SWAT used in many drug busts

Standard police units still carry out search warrants for drugs.

But sometimes they request SWAT backup, said Capt. Jay Edwards, who is responsible for signing off on the use of SWAT units: “If a unit, based on the totality of the circumstances around that particular investigation, deems that they don’t feel like it’s safe for them to do it with the equipment that they’re assigned, they may ask us to look at it.”

Ultimately, protecting the safety of the police officers, suspects and general public is the primary purpose of the SWAT team, said Wilson Weaver, an assistant police chief.

“In our city, with 230,000 or so citizens – we’ve got violent people in the city. When they’re committing crimes, we’ll utilize our SWAT personnel, who have the equipment – and I’m not just talking guns, but also ballistic-protection equipment for themselves. They’ll use their knowledge, experience and training to apprehend those people safely and not put anyone in danger. That’s the purpose of the SWAT team – it’s saving lives.”

The Winston-Salem Police Department may run the best SWAT operation in North Carolina, and the use of SWAT teams for drug raids may be warranted.

Then again, it may not.

There isn’t enough information available to the public to tell with any certainty, according to the American Civil Liberties Union of North Carolina. And oversight by public bodies – in this case, the Winston-Salem City Council or its public-safety committee – is lacking. Sarah Preston, police director at the ACLU-NC, said that the information received by the Journal on the use of SWAT teams is similar to that received by the ACLU in a report titled “War Comes Home: The Excessive Militarization of American Policing.”

The ACLU started its investigation last year after hearing complaints about excessive use of force.

“Community policing is having the community involved,” Preston said. “A community should have access to information about how this is being carried out: What tactics are being used? What weapons?”

After reviewing 800 SWAT raids in 20 states, including North Carolina, the organization found that police departments use their militarized SWAT teams mostly to execute drug search warrants – 79 percent of the time – not for unusual occurrences such as situations involving hostages or active shooters. The report also found that minorities are being disproportionately targeted.

Public needs to know more

The city could provide the public with a glimpse into information about the race of the suspects involved in SWAT operations, according to Amanda Martin, an attorney who specializes in state public records laws. State law does not prohibit the city from providing that type of information. But the city did not do so when asked by the Journal.

The city also did not agree to the Journal’s request for After Action Reports, which contain a brief description of the incident, participants, tactics or actions taken and a critique of the event.

“The city’s standard practice is to provide the public with material that is listed as public record under state law,” said Lori Sykes, a city attorney who works in the police department, responding to the request for information on race of suspects. “We do not believe the After Action Report is the type of document or information referenced in subsection c of GS 132-1.4,” referring to the section of general statute governing public records in crime reports.

As a result, the Journal was not able to find out many things: How many SWAT members were involved in raids. What equipment was used? Flash-bang grenades? The BEAR? What was the race of suspects?

Rather, the city provided information related to time, date, charges and suspect, among other details. A map of the 40-plus incidents involving SWAT shows that while many of the deployments involved what police officials say were dangerous suspects and drugs over the course of a year, those deployments took place often in minority neighborhoods. Apparently, there weren’t any drug search warrants that required the use of SWAT along Polo Road, Country Club Road or Robinhood Road, among other main roads in mostly white neighborhoods. Many of the deployments straddled University Parkway, Waughtown Street and New Walkertown Road.

Another question remains open: Was the use of SWAT necessary?

Police officials have said that they work on the “totality of information.” If a suspect is dangerous, then SWAT is called in. Sometimes, the information appears to be flawed, according to the documents obtained by the Journal. In the 40-plus incidents involving SWAT, close to one-quarter of the deployments led to no arrest.

City council has oversight

During the Journal’s request for public records, City Manager Lee Garrity said that city staff would present the ACLU report to the city council’s public safety committee in August.

James Taylor, the chairman of the public safety committee, said that during his time on the council, since 2008, there has not been a comprehensive discussion, or progress report, on the use of SWAT by the police department. He said he did not know how many times SWAT had been deployed during the past year. “Until you raised some of these questions, I haven’t really thought about it,” he said.

As someone who grew up in the Southeast Ward, which he represents, Taylor wants to get drugs out: “If SWAT can stop it, I’m all for it.”

And he wants more information to be public about SWAT – “the good, the bad and the ugly.”

“We will do a better job of getting information from the police chief. I intend to ask the police chief for an update,” Taylor said. “I want the bad guys to know there is a SWAT unit.”

No comments:

Post a Comment