12/30/2014

Just a short time earlier, I couldn’t answer the man who, on the behalf of the women and families in his village, asked what HLI could do to help them. In truth, our country director, Father Jonathan Opio, has already begun to help by coordinating with medical professionals and training new Natural Family Planning teams. But there is so much more to do.

Just a short time earlier, I couldn’t answer the man who, on the behalf of the women and families in his village, asked what HLI could do to help them. In truth, our country director, Father Jonathan Opio, has already begun to help by coordinating with medical professionals and training new Natural Family Planning teams. But there is so much more to do.

source

Only an hour ago we had been lamenting yet another incredibly bad road. Here in the Ugandan outback, it is as pointless to complain about the roads as it is to complain about politicians in America, but railing against the unchangeable can lighten the mood.

But on the way out of a small village in the Bukedea region of Uganda, we didn’t feel the bumps. That was when our team’s defenses failed, and when the gravity of the assault on women—perpetrated by the champions of “women’s health” and “empowerment”—really hit home. It may have been just me, but my guess is that we were all a little numb.

Just a short time earlier, I couldn’t answer the man who, on the behalf of the women and families in his village, asked what HLI could do to help them. In truth, our country director, Father Jonathan Opio, has already begun to help by coordinating with medical professionals and training new Natural Family Planning teams. But there is so much more to do.

Just a short time earlier, I couldn’t answer the man who, on the behalf of the women and families in his village, asked what HLI could do to help them. In truth, our country director, Father Jonathan Opio, has already begun to help by coordinating with medical professionals and training new Natural Family Planning teams. But there is so much more to do.

To understand why we were at a loss for words, let me tell you what we found on our ten-day trip through Tanzania and Uganda, in speaking with women who had been harmed by long acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs). There were several themes that emerged as we interviewed over 60 women and spoke to almost 300 who were willing to break cultural traditions to tell complete strangers about their ordeal.

Women, often without their husband’s knowledge, go to an information session at a clinic of some kind—often a government clinic (although “government” here is a relative term since the non-governmental organizations who provide these drugs are so intertwined with the government). The women are told that the best way to get out of poverty is to do what we do in the West—to stop having kids, or to “space pregnancies.” They are pressured, sometimes very strongly: We spoke to four women who said they were locked in a room until they “chose” a method, and the method they were forced to choose was an IUD. In most of the other cases, the victims were not told about possible serious side effects before being given the contraceptive method—usually the injectable Depo Provera (sometimes called Sayana Press), Norplant (rods inserted in the upper arm, often leaving ugly scars), and IUDs—and sent on their way.

Not one woman reported being asked for her medical history. Many said they were surprised how impersonal, how rushed, and sometimes how rough the process was. Some reported being okay for a year or more on a certain method before side effects started appearing. The most common side effects seemed to be severe, prolonged bleeding (for Norplant, it was often the absence of a period for over a year, until seeking its removal); loss of energy; loss of libido; blurred vision; headaches; and leg pains.

Some had stopped using the method and were feeling better, but many of them were in continuing agony, and many were very sad or angry. It’s one thing for a woman in the U.S. to deal with these side effects, though she probably would have had to be told about the risks, and she would have at least had a chance to see the huge disclaimer inserts in the package. But for rural African women, there is no medical infrastructure. Most women in the U.S. can go back to their doctor, get another method, go to the corner drug store and pick it up for a small co-pay on their insurance. The American woman has a laundry machine in her air conditioned home and other medicine to hide or mitigate the symptoms. She can deal with it privately and seek help or seek an attorney if it’s bad enough and if she thinks she was misled.

Very few, if any, of these women we met in Tanzania and Uganda have any of this available to them. Often, their husbands beat them up for not telling them they were going to use the method. This was very common, and there is no way to seek justice since “that’s just how it is” in a culture where women are second class citizens. If she is bleeding non-stop and/or loses her libido, the man often kicks her out or shacks up with another woman, and the whole village knows it. The woman is shamed, and if she can’t work—as work is the sole way of measuring a woman’s value in many of these places—she is further shamed as a drag on the family and the village. She has no laundry machine or few spare clothes to hide what is happening to her body. If she goes back to the clinic (which many don’t do, sometimes thinking they’ve been “bewitched,” not associating their symptoms with the drug that they were told would only result in good things), she is told to wait it out. If, however, she is persistent, she is told to come up with a whole lot of money — maybe the equivalent of $30 U.S., but in villages where cash is not normally transacted, this is a huge amount of money — for “treatment,” which is often just The Pill to stop bleeding or some other method that may or may not work.

Here’s the point: The method is given free of charge—the treatment is not. Several women told us they went to the clinic and after being denied treatment, either threw a fit that shamed the staff into helping them, or were hauled away by police, and a couple of them were beaten up. The people doing this apparently have zero consideration for side effects and ongoing wellness care with the victims.

We talked to a representative of the reproductive health industry who came to tell their side of the story at an event held by our affiliate. Whenever we asked her about side effects, she would say that the problem was one of “a lack of education,” as if that was an answer. It was surreal. Again, we have no way of telling how widespread all of this is, though I should note here that the largest-ever campaign to promote these dangerous drugs, called Family Planning 2020, has as its goal to “help” 120 million poor women to start using these drugs in the next six years. But we were shocked how many women were willing to risk the shame of coming forward to tell their stories in public. And, tellingly, the folks perpetrating this have no data either on side effects or ongoing wellness concerns for their “patients.” They don’t seem to care.

So the effects are physical, but have a domino effect in the lives of rural women that is quite devastating. We went to a deep rural Ugandan village with a government clinic, and by the time we left we had 20 women wanting to talk with us—and they were only the ones who had the temerity to do so.

This must stop. All I could tell the village leader who asked me, “What can you do?” was, after a long pause, that I would try to tell their stories. And that is exactly what we will do. We are compiling our interview footage and will expose the harm being done to women under the viciously ironic title of “reproductive health.”

We are also beginning to work through a fuller response—one possibly involving partners who are medical missionaries; who can train local nurses, midwives and doctors to recognize and treat symptoms; and who can teach healthy sexuality for married couples, which would include evangelization. For all of these efforts we ask for your prayers and that you follow HLI on email and social media, where we will announce developments.

Basically, women are being treated like cattle—sterilized by hacks and left to fend for themselves—as part of a campaign led by very wealthy nations and NGOs who think sterility is the key to progress and development. I think many of those involved think they’re doing good, but if this is the case, where is the follow up for these women? This is what we can’t figure out. Why aren’t we seeing more care in how this happens, rather than what we are actually seeing: huge increases in funding to grow exactly these kind of corrupt, anti-woman sterilization programs?

Ultimately, our friend’s question applies to all of us: What can we do?

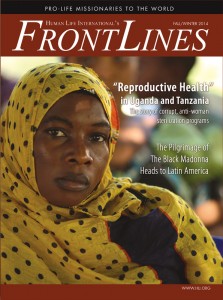

LifeNews Note: Stephen Phelan is the communications manager at Human Life International.Reprinted with permission from Human Life International’s World Watch forum. This article was originally printed November 2014 in Frontlines, Human Life International’s full-color magazine.

source

No comments:

Post a Comment