2/15/2015

source

THIS month Al Arab, a new private Saudi-funded satellite channel, launched in Bahrain with shiny new studios and sparkling ideals. It would, said Jamal Khashoggi, the veteran Saudi journalist appointed to head it, be the “voice of the voiceless”. Not for long. Just six hours after Al Arab first went on air the Gulf statelet gagged it; on February 9th authorities said it must close for good, claiming it was not properly licensed. Its real sin, it seems, was to give airtime to Al Wefaq, Bahrain’s main opposition party.

The short life of Al Arab is emblematic of a wider flowering of independent Arab media, and its subsequent withering. The channel took shape during the heady days of the Arab spring, when autocratic regimes were falling and people yearned for free media. Appetites had been whetted since the early 1990s, with the advent of the internet and satellite TV.

Some regard the mother of all independent Arab media to be Al Jazeera, a pan-Arab television station that first broadcast in 1996. Although funded by the ambitious rulers of Qatar, it broke the mould of Arab journalism, which then consisted of little more than reheating official press releases. The station’s professional journalists, top-class technology and feisty talk shows set a new standard for freedom of expression. Audience figures rocketed to tens of millions as it won scoops that included airing video and audio tapes of Osama bin Laden, the late head of al-Qaeda.

By 2011 it was playing a role in fomenting the Arab spring by streaming live footage of protesters from Tunis to Tripoli. Such was its clout that others tried emulating it, not least Al Arabiya, a Saudi-owned broadcaster that came on air in 2003. But Al Jazeera’s influence has since waned amid perceptions that its journalism has turned partisan. Even as it championed Syria’s mainly Sunni rebels, some of whom were later financed by Qatar, it ignored Bahrain’s mainly Shia uprising.

The most acute criticism surrounds Al Jazeera’s kind treatment of Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood, a line that corresponded closely with Qatar’s foreign policy. The station fawned over Muhammad Morsi, a Muslim Brotherhood member who was elected president of Egypt, and decried his ousting by the army as “a coup against legitimacy”. Al Arabiya, meanwhile, followed Saudi hostility to the Brotherhood, calling the event a “second revolution.”

And as Al Jazeera once provided a model of free speech, local regimes are now seeing in it a model for propagating their own views across the region. Iran and Syria backed the launch in 2012 of Al-Mayadeen, a pan-Arab satellite channel based in Beirut. They hope it will counter the Gulf channels that are inimical to Bashar Assad, Syria’s president. A journalist at Al Modon, a Qatar-funded news site, says it was launched partly to counter Saudi Arabia’s media influence in Lebanon.

A loss of trust in the impartiality of satellite TV is all the more worrying because it had been seen as an alternative to local media long cowed by authoritarian governments. When Abdel-Fattah al-Sisi, Egypt’s army chief (and now president) came to power he quickly closed down Islamist television stations. Three Al Jazeera journalists were imprisoned in Egypt for more than a year on spurious allegations of belonging to a Muslim Brotherhood cell. In Syria Mazen Darwish, who headed the Centre for Freedom of Expression, is just one of 12 journalists in Mr Assad’s jails; others have their work stymied by rebel militias. In Saudi Arabia four journalists have been jailed after covering Shia protests in the eastern province.

Little wonder that much news broadcast on local channels is mind-numbingly dull. In Saudi Arabia television stations mainly offer religious fodder and reports of royal beneficence. In Jordan the front pages feature glowing tales of the royal court. When not boring, state output is often shockingly mendacious. Syrian state television once claimed Al Jazeera was building sets of Syrian cities so as to stage fake protests. Private media is often little better since it is owned by big businessmen whose interests usually lie in buttering up regimes. CBC, a private Egyptian channel founded in 2011 by Muhammad al-Amin, offered airtime in November 2012 to a hugely popular sketch show by Bassam Youssef, akin to America’s Jon Stewart. But a year later, with Egypt under new management, the channel ended the show. In 2013 ONTV, another private channel, lost Reem Maged, an Egyptian presenter known for hard-hitting interviews, when she cited differences between her interest in free journalism and the channel’s focus on “national security”. “Everyone is taking their cues from the regime,” says Rasha Abdulla, a professor of journalism at the American University in Cairo. “The situation is worse today than ever.”

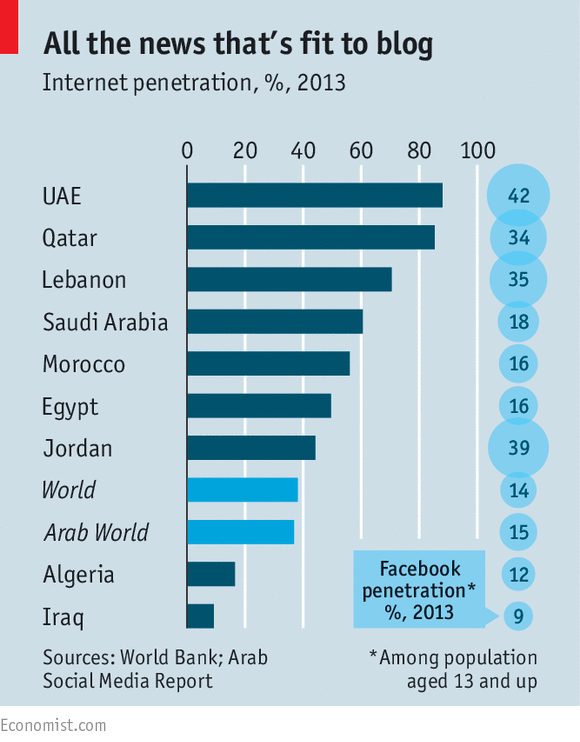

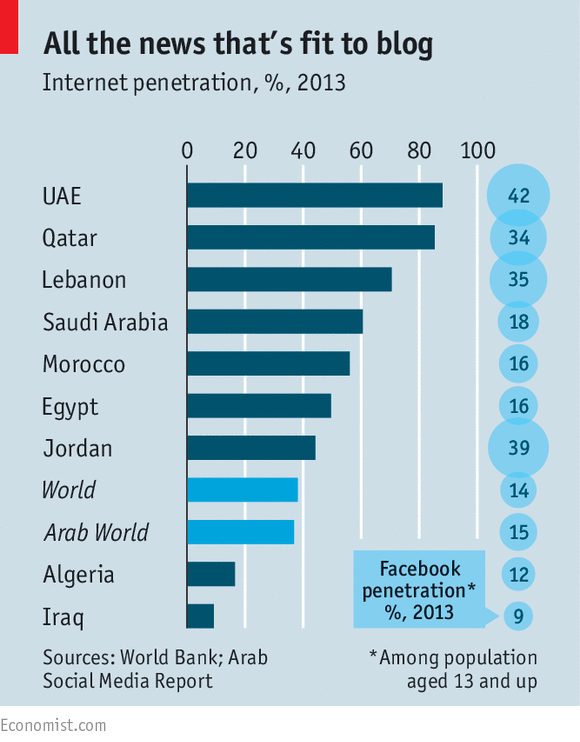

One ray of hope is that people increasingly seek news online, where resources and wannabe journalists have proliferated since the Arab spring. Internet access is surging across the region (see chart) and is used particularly by young people in places like Saudi Arabia to find alternative sources of news. These include social media and small independent outfits. One such is Mada Masr, a newspaper in Egypt that manages to push boundaries, perhaps because it is written in English. Networks in rebel-held Syria broadcast local news via YouTube channels or Facebook pages; a few including Aleppo Today broadcast on satellite. But even new media fall into the habits of their older brethren, such as uncritically airing conspiracy theories, however outlandish. Depending on which newspapers or websites you read in the region, you will believe that the jihadists of the Islamic State are either a creation of wealthy Gulf states, Iran, Israel’s Mossad, the CIA, or some bewildering combination of the three.

Such silliness may not quite accord with the Jeffersonian ideal of a free press acting as a guardian of liberty. But better a cacophony of dissenting voices— online or beamed from satelites—than the stifling monotone of state-controlled or cowed media. “Today there is much less power concentrated in state-owned media and traditional gatekeepers,” says Habib al-Battah, a Lebanese investigative journalist who runs the site Beirut Report. These days, says Mr Battah, the region’s people “are sophisticated consumers” who browse several news sources to distil the truth. The genie of feisty and critical media may be stuffed back into the lamp, but not the thirst for information.

source

No comments:

Post a Comment